A CONVERSATION with FREDERIC C. RICH

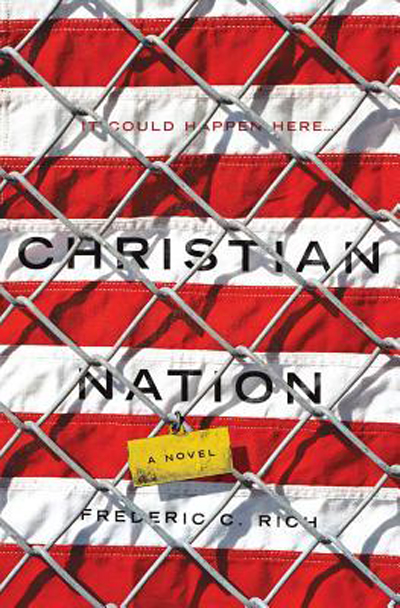

Q: What is your novel, Christian Nation, about?

A: The novel is fundamentally about the danger of complacency in the face of religious fundamentalism. It shows how the Christian right could obtain power, and what they would do with it if they got it. The Christian right has worked for more than three decades to acquire political power in America; they’ve already succeeded in high jacking one of our two major political parties. So the book begins with these facts, and then tells a fictional story: a story of how, influenced by extreme fundamentalists, the Christian right could succeed in implementing a theocratic agenda in America, and what life would be like if they succeeded.

Christian Nation also challenges the reader to think about how they as individuals would react if this started to happen; the book is fundamentally about personal responsibility in the face of a great social or political evil.

Q: You say theocracy. Isn’t that a bit extreme? What do you mean by theocracy?

A: I mean a state where law and policy are based on the sacred texts of a single religion, and government officials purport to speak to and for God, thus claiming the mantle of divine authority. A Congressman from Georgia, Paul Broun, said the other day that he regards “the Holy Bible as being the major directions to me of how to vote in Washington, D.C.” Sarah Palin claims that she talks to God and then tells us what God wants. When the people in control of the country think the same way, you’ve got a theocracy.

Q: You just mentioned Sarah Palin. What is her role in the novel?

A: Although the book is fiction, it records the Christian right’s quest for power quite accurately up to a point, and then speculates about what could have happened if a certain event had turned out differently. In this case, my counterfactual is that McCain/Palin, and not Obama/Biden, won the 2008 election. It easily could have happened. Then, what really makes things interesting is that McCain dies within a few months of the inauguration, and Sarah Palin becomes President. Just think about it—this easily could have happened, too.

Q: The novel makes lots of references to the rise of fascism in Germany. Are you saying the Christian right are like Nazis?

A: No, but I am saying that extremist ideologies flourish in the soil of economic suffering, national self-doubt, fear and distress. And yes, the conditions in Germany in the 1930’s—in which fascism was able to take root in a perfectly sane, well-educated country with a large middle class—are similar to what we might suffer here with economic mismanagement and some bad luck. Let’s not forget the extent to which fascism flourished in America during and after the Great Depression. Most authoritarian regimes take power in free elections in conditions of great social and economic distress.

Q: Why did you decide to write Christian Nation?

A: Over the Bush years, there were a series of moments, like watching President Bush explain to the nation whyvernment would seek to ban stem cell research, when I had a strong sense that our own home-grown brand of religious extremism was driving policy and politics. This really scared me. But it wasn’t until Sarah Palin was selected by Senator McCain that I was moved to act. I knew quite a bit about Palin’s fundamentalist religious beliefs, her extraordinary ignorance, and her lack of competence, so her nomination really astonished and scared me. I decided I had to do something.

Q: There have been many non-fiction books about Palin and the theocratic aspirations of the Christian right. Why write a novel?

A: You’re right. I devoured great books by Chris Hedges, Michelle Goldberg, Jeff Sharlet, Max Blumenthal, Kevin Phillips and others. They are first rate journalists and scholars, and the story they told about the political aspirations of the Christian right was terrifying. But I couldn’t believe how little impact those books had. Most of my friends in New York are great readers, and politically active people, yet none of them knew about dominionism, reconstructionism or the theocratic theologies that inspire growing numbers of evangelicals. They didn’t know about the hostility to the separation of church and state. And none of them understood how strong the movement was, or how much progress it has made in acquiring control of the Republican Party, many state legislatures, and influential positions in Washington.

I have always believed that art and literature are stronger than journalism and scholarship; art and literature can move people where their deepest views and opinions are formed, through emotion, intuition and identity. So I got the idea of telling the story in the form of a novel, using characters who grapple with what to believe and what to do. And who suffer when the Christian right’s agenda is finally implemented.

Q: It seems from the book that you think gay men and women have the most to lose.

A: Yes. The cause of gay rights is making great strides in this country – look at the incredible success with marriage equality in the 2012 elections. But this trend sometimes obscures another: that a very significant percentage of the American population is not only opposed to civil rights for homosexuals, but believe that homosexuality is a sin that will bring the wrath of God upon the country. This is a politically powerful belief. All nascent populist and authoritarian political movements need an enemy, and for the Christian fundamentalists the enemy is the gay Americans.

Q: What’s your own religion?

A: I was raised in the Roman Catholic Church, but now I’m an atheist. I have always been interested in morality and ethics. I did my graduate work before law school in moral philosophy, and believe that morality is central both to personal happiness and a successful culture.

Q: What about your own politics? Some people may think that you wrote this to discredit the Republican Party.

A: Not at all, and in fact during the time I was writing the book, I was still registered as a Republican, as I was for most of my life. But the most recent Republican Presidential primary season—with the party fielding people like Bachman, Perry and Santorum as serious candidates—it was just too much, and I switched to independent.

Do I want people to think about what the Republican Party has become, having been largely hijacked by the Christian right, which is now joining forces with the Tea Party? Absolutely. Too many good moderate Republicans just don’t see it. But I certainly don’t want to see the Republican Party destroyed. We need two credible mainstream parties in this country for our political system to work. I want to see the Republican Party get back in touch with its libertarian side, which of course believes that government should not be telling us what we can do in our bedrooms, whom we can marry or what we can read.

Q: There have been several popular works of political fiction over recent years. What sets Christian Nation apart?

A: You’re right – David Frum published Patriots last year, of course there was Primary Colors in 1996. Even Ralph Reed wrote a novel about a Supreme Court nomination battle. But these are all “inside baseball” books: the authors are political operatives, and the characters are politicians and political operatives. In contrast, CHRISTIAN NATION’s characters are ordinary people who are trying to make their lives against the backdrop of the world the politicians are giving them, and who, eventually, are roused to action.

I would compare Christian Nation to books like Sinclair Lewis’s It Can’t Happen Here. He was worried that Americans didn’t take the threat of fascism seriously enough, so he showed the country in a novel how it might happen and just what it could mean. Or, another example is Philip Roth’s Plot Against America – that was historical, of course, but also a what-if book, like mine, based on the counterfactual that Charles Lindbergh won the 1940 election.

Q: Ok. But the idea of a fundamentalist theocracy in America -- like the Taliban in Afghanistan, or in Saudi Arabia or Iran -- it’s just so farfetched.

A: Fair enough, but you have to remember that this book is not a prediction. I don’t think we are going to have a fundamentalist Christian theocracy in America, either. But I do think that with some bad luck and bad decisions, it’s possible, and that’s what scares me. In the book Adam asks Greg, “What happened, why did it happen, how could it have happened?” This is the question that Hannah Arendt asked herself after the defeat of fascism, and is the most important question, really, of the 20th century. I want to make sure we don’t find ourselves asking that question again in the 21st century.